hippie counterculture, moral panics, and lsd

Contents:

Introduction: Not Satan?

Media, Science, Governments, and LSD: How Fast Can Opinion Change?

Banned but Never Abandoned: Hippie Culture Turns Counter

The End?

this is an old history piece about the LSD/counterculture movement, how it was villainized and led to a variety of different outcomes for hippies and on protest culture. I wrote this a while ago (so my opinions on a few things have likely changed!) and I just wanted to post it so I could send it to people :). The formatting on my substack post for this is better, with linked footnotes.

1: Introduction: Not Satan?

If you were to read the headlines of any major magazine of the 1960s, you might genuinely believe that America was in the midst of fighting some Satanic force. Headlines like “America’s Most Dangerous Drug,” “Devil Worship: Exposing Satan’s Underground,” "Strip-Teasing Hippie Goes Wild on LSD,” and “Lock ‘Em Up and Throw Away the Key!” overtook periodicals in response to a hallucinogenic drug that had begun to spread across the nation: LSD.1 This fear was founded on the irrational belief that LSD and the hippie counterculture that embodied it, would take over the nation. As sociologist Barry Glassner puts it, Americans are accustomed to living in a “culture of fear.”2

During the 1960s, the public’s disproportional and blind belief in the demonization of LSD by governments, the media, and the scientific community led to an abrupt criminalization of hallucinogenic substances and their consumers, proof of America’s tendency for unjustified national moral panic, which, in this case, was towards the hippie and activist Yippie counterculture movement. Sociologist Erich Goode defines a moral panic as “a scare about a threat or supposed threat from deviants… [who] are blamed for menacing a society,” but this hostility is wildly “out of proportion to the actual threat that is claimed.”3 That was exactly what happened: the media over-reported minor incidents and, later, outright false information.4 Congress passed legislation that severely disadvantaged specific demographic populations in an attempt to stop and eventually criminalize the use of LSD. Even scientists turned their back on valid acid research, too influenced by the various LSD scares. More broadly, Hippies quickly fell victim to police brutality and government-sanctioned exclusion.5 What was likely a major factor in the pushback against LSD were the Yippies, a protesting and activist Hippie group, that threatened those in positions of power. Interestingly, the RAND Corporation published a 1962 report that argues that LSD alters “attitudes, values, and communicative ability” and therefore contributes to activism in users.6

Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann first synthesized LSD, or Lysergic Acid Diethylamide, in 1938 when trying to develop a nervous system stimulant at Sandoz Pharmaceuticals.7 Unintentionally, he synthesized a hallucinogenic, psychedelic drug that is now often also referred to as acid or psilocybin. Disappointed by its ineffectiveness, Hofmann set LSD aside until five years later, in 1943, when he accidentally absorbed some of it through his fingers when reexamining the drug. He described the mind-blowing sensation as “like [perceiving] an uninterrupted stream of fantastic pictures, extraordinary shapes with intense, kaleidoscopic play of colors.”8 Three days later, Hofmann intentionally ingested 250 mg of LSD to experience the sensations again, later to be commemorated as the first time acid was ever ingested deliberately.9 After Hoffman’s discovery, it took another five years for LSD-25 to reach scientists in the United States, and thus began the spread of psychedelics across the nation—a movement that led not only to a moral panic but also criminalization of an entire subset of society—all within approximately a decade.10

2: Media, Science, Governments, and LSD: How Fast Can Opinion Change?

Surprisingly, public media initially praised LSD for its benefits and supposed magical ability to change minds. In 1959, This Week wrote that LSD “has rescued many drug addicts, alcoholics, and neurotics from their private hells—and holds promise for curing tomorrow’s mental ills.”11 From 1959 to 1961, the majority of articles on psychedelics extolled its benefits for drug addicts and mentally ill patients, but any attention was few and far between. That was, until the 1963 firing of Harvard psychologist Timothy Leary and the end of the Harvard Psilocybin Project, a seminal research project that defined public perception of LSD for years to come and showed how fast public opinion can change.

The Harvard Psilocybin Project (HPP) was first started in 1961 by Tim Leary and Richard Alpert, two ambitious psychologists interested in going beyond clinical psychology.12 A surprisingly large number of students and faculty at Harvard shared their passion for researching the effects of psychedelics, making it easy for their project to get started.13 HPP enlisted Cambridge students and conscripted inmates at the Lexington Narcotics Hospital to study various reactions to taking psilocybin.14 Their work focused on the relationship between drug-induced and naturally occurring religious experiences as well as determining if LSD had any behavior-changing effects. Leary and Alpert found that someone could “be a convict or a college professor… [and] still have a mystical, transcendental experience that may change [one’s] life.” This particular aspect of LSD was what made it simultaneously so attractive to the general public yet so threatening to those in power. Unfortunately, Leary and Alpert’s experimentation on prison inmates and, even worse, Harvard’s own undergraduate and graduate students led to criticisms from other faculty. A month after a 1962 faculty meeting where various colleagues voiced their concerns, Harvard informed Leary he could no longer continue his research.15

Harvard University’s willingness to reject something they had widely approved of only a year before reflected the evolving attitudes of the American public. A good example for this is the dramatic progression of headlines over the span of two years. In 1965, Time ran a cover story titled "The Psychedelic Revolution: Are Drugs Turning On The World?"16 This seminal article brought widespread public attention to the growing use of LSD and other psychedelic drugs, especially in positive contexts. Around this same time, media coverage of the Beatles’ use of LSD increased public interest in the drug even further. In 1967, Life magazine ran a cover story about LSD with the headline “LSD: The Long Trip.” This article described LSD as a “potent weapon for mind control” and claimed that it could lead to "insanity or suicide."17

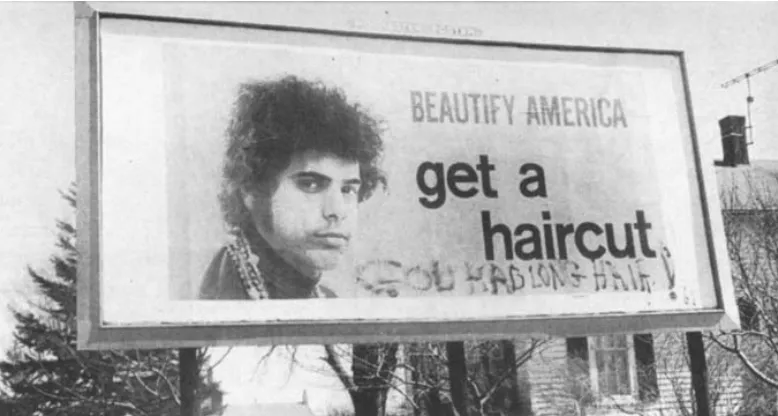

Figure(s): Anti-Hippie billboards were placed around the nation as part of a project led by John Donnelly & Sons.

It only took two news stories published within the same year to shift media perception entirely. In April 1966, a 5-year-old Brooklyn girl suffered convulsions after swallowing an LSD sugar cube left in the refrigerator by her uncle.18 A week later, police charged former medical-school student Stephen H. Kessler for stabbing his mother-in-law to death. He claimed he was unaware of his actions because he had been high on LSD for three days prior.19 Countless papers reported these two events that snowballed into a widespread attack on LSD itself. Propagandistic statements such as “if you take LSD, even once, your children may be born malformed or retarded” were published as scientific truth, even though there was little to no actual scientific proof.20 As negative sentiments towards LSD spread, Sandoz Pharmaceuticals revoked their new drug application for LSD, and by June 1966, magazines were decrying the villainous effects of psychedelics. Headlines like “Thrill Drug Can Warp Minds and Kill,” “LSD: For the Kick that Can Kill,” and “Strip-Teasing Hipping Goes Wild on LSD” were plastered on the front pages of magazines such as Time or The Atlantic.21 The blind belief in such news led even pro-drug and pro-marijuana counterculture magazines like the East Village Other (EVO) to write articles about LSD’s alleged effects on brain growth, such as “Acid Burned a Hole in My Genes.”22 Although the EVO was “a… newspaper so countercultural it made The Village Voice look like a church circular” and was incredibly influential in the 1960s, yet it still fell for the inaccurate, biased reporting of the time.23 The ease at which even the staunchest LSD supporters could turn against it only serves to prove how easy it is to manipulate the public into a moral panic.

The flood of negative media attention rapidly brought LSD to the attention of drug enforcement agencies. Nevada and California became the first states to outlaw the possession, sale, and manufacture of LSD on May 30, 1966.24 Other states quickly followed suit, and by 1968, LSD was classified as a Schedule I drug by the United States Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), legally defining it as a drug with a “high potential for abuse” and with no function in any medical treatment.25 Suddenly, the movement that had created social phenomena such as the Electric Acid Kool-Aid Test and inspired bands like The Beatles and Pink Floyd became a counterculture movement persecuted by the government and the broadscale public.26

Perhaps most concerning was the lack of reputable scientific data to stop any of the government’s legal decisions. A landmark 1967 scientific article titled “Chromosomal Damage in Human Leukocytes Induced by Lysergic Acid Diethylamide” was published in Science, one of the most reputable sources of scientific knowledge. Soon, many more papers were published claiming LSD-25 caused not only genetic abnormalities but also congenital abnormalities and developmentally delayed children. Future investigations found these science reports to be minimally peer-reviewed, and when future researchers tried to replicate the experiment, the results were found to be drastically different.27 That single scientific article soon led to a slew of anti-LSD scientific articles, further claiming that any use of LSD will lead to internal cell combustion. In the subsequent months of 1967, the New York Times published “LSD Peril found in tests on rats” and “Congenital disabilities to offspring added to peril”; the Los Angeles Times wrote articles like “Dangerous cell reaction in use of LSD reported” and “Harm to chromosome observed in LSD users,” amongst countless others. What is compelling is how the media and scientific community alike chose to base their coverage on unverifiable claims. One journalist reported that a psychiatrist declared that “nobody comes back unharmed. In every case [of LSD usage], there is some degree of brain damage,” but when pushed for sources, the psychiatrist revealed that it was merely hearsay upon hearsay—no factual scientific basis.

3: Banned but Never Abandoned: Hippie Culture Turns Counter

Walk into any shopping mall today, and you will find rows upon rows of t-shirts with psychedelic fonts or merchandise for legendary bands like The Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, or Jimi Hendrix. These artists all found their first followers through psychedelic music and later became figureheads for the counterculture movement.

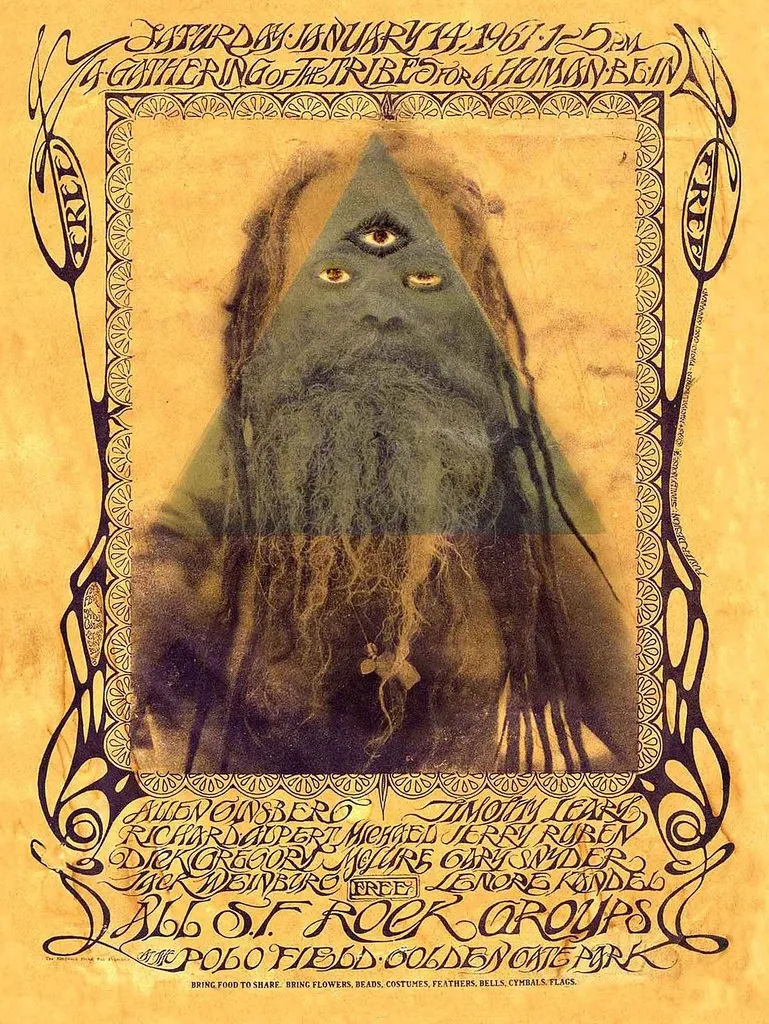

The soon-to-be persecuted Hippies soon became closely tied with activism—especially in protest to the United States’ involvement in the Vietnam War. Their questioning of governmental actions overseas became a signature of an entire generation’s “culture… of dissent.” Massive gatherings known as “Be-ins” soon became a place for people to gather, either as part of a music festival, an art show, a protest, or merely a way to celebrate life, often while dropping LSD (see Appendix A). The first such event was the January 1967 “Human Be-in” in the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco, which subsequently became synonymous with Hippie culture. The media and the public were stunned by the mass migration of young people to the district and the radical New Left politics that this new movement embodied. Unfortunately, it also drew the ire of police forces who felt justified in meeting these supposedly “Satanic people” with brutality and animosity.

What police claimed to be in the name of protecting the public, was, in fact, social control. Sociologist Michael Brown identifies four aspects of repressive social control: 1) the administration of control is suspicious; 2) it requires bringing together previously hostile groups; 3) control grows until it encompasses everything; and finally, 4) control is relentless. In the summer of 1968, street sweeps, drug busts, and the ominous presence of tactical police forces became commonplace on America’s streets. More telling, police used arrests as a form of control—they were “regularly accompanied by beatings and charges of ‘resistance to arrest’—inspiring private citizens to take the law into their own hands. After a police assault at a 1967 gathering in Tompkins Square Park in New York City, rapes and assaults were reported as being justified in the name of the “defenders of the faith.”

Authoritative inaction and denial only served to enable these grave injustices. New York Mayor John Lindsay referred to the Tompkins Square assault as a “free wielding of nightsticks,” and the Chief of Police in San Francisco told The New York Times that “Hippies are no asset to the community.” This violence escalated into even more widespread hate and retaliation. Billboards were put around the nation carrying slogans like “Keep America Clean: Get a Haircut,” and signs were put up in restaurants saying, “Hippies not served here.”

The phenomenon of a counterculture is intriguing. When a culture becomes counter- or alternative, it becomes a new conceptual system and an identity. Before the criminalization of psychedelics, for example, many young Hippies turned against the movement after a bad acid trip. However, once the Hippie identity became synonymous with an expression of dissent and shared trauma, it also became a movement of interdependence and trust. Mainstream news and media may have continued to demonize LSD, but the subsequent flood of underground media, rock music, art, and activism only strengthened the community from within.

Yippie lead activist Jerry Rubin, in an open letter to “[his] brothers and sisters in the movement,” called for his “family” to come together and “fulfill [their] destiny in life by rejecting a system which rejects them.” Though the brutal treatment of hippies, especially of youths and disadvantaged communities, was deplorable, it also helped these groups come to a collective understanding that there should be change within the nation.

4: The End?

Hippies may not be Satan’s spawn, as people liked to claim, but they did spawn a movement that had long-lasting impacts that we still feel today. The almost horrifyingly fast descent into hate and vitriol shows how fast the world can turn against a group of people and how susceptible this system is to misinformation and manipulation. There is no easily attributable cause for this descent; rather, it was due to a combination of spectacle-chasing news articles, scientific papers published with minimal peer review, and government action with ulterior motives.

The emergence of the Yippie counterculture movement can also teach us much about today’s movements. Through shared struggles and trauma, Hippies found a sense of identity. Their activism inspired many future movements by showing youths that change is required for the world to become a better place.

Figure: Poster advertising the famous Human Be-in in San Francisco (Golden Gate Park/Haight Ashbury), advertising the presence of various famous rock bands, artists, figureheads of the movements, and more.

To learn more, read:

Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test by Tom Wolfe.

Acid Dreams: The Complete Social History of LSD by Marine A Lee and Bruce Shlain

Jack Kerouac and the Beat Generation (the predecessors!) and his close ties with Allen Ginsberg

LSD, My Problem Child; And, Insights/Outlooks by Allen Hofmann

Revolution for the Hell of It by Abbie Hoffman

Moral Panics: The Social Construction of Deviance by Goode, Erich, and Nachman Ben-Yehuda

LSD by Richard Alpert, Sidney Cohen, and Lawrence Schiller

And of course, here is the link to my nbligatory playlist: link.

References / Footnotes

Here’s a simple ordered list of the references:

- Erich Goode and Nachman Ben-Yehuda, Moral Panics: The Social Construction of Deviance (Oxford, UK; Cambridge, USA: Blackwell, 1994), 89.

- Barry Glassner, The Culture of Fear: Why Americans Are Afraid of the Wrong Things (New York: Basic Books, 2018).

- Goode and Ben-Yehuda, Moral Panics, 7.

- Martin A. Lee and Bruce Shlain, Acid Dreams: The Complete Social History of LSD (New York, NY: Grove Press, 1992), 194.

- Michael E. Brown, “The Condemnation and Persecution of Hippies,” Society 6, no. 10 (September 1969): 33–46, https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03180973, 37.

- William H. McGlothlin, “Long-Lasting Effects of LSD on Certain Attitudes in Normals” (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 1962).

- Richard Alpert, Sidney Cohen, and Lawrence Schiller, LSD (New York, NY: New American Library, 1966), 5-20.

- Albert Hofmann, LSD, My Problem Child; And, Insights/Outlooks (Oxford: Beckley Foundation, 2019), 15.

- Alpert, Cohen, and Schiller, LSD, 15-20.

- Martin A. Lee and Bruce Shlain, Acid Dreams: The Complete Social History of LSD (New York, NY: Grove Press, 1992), 19-20.

- William Braden, The Private Sea: LSD and the Search for God (London, Pall Mall Press, 1967), 197.

- Andrew Weil, “The Strange Case of the Harvard Drug Scandal,” www.psychedelic-library.org, 1963, http://www.psychedelic-library.org/look1963.htm.

- R. Gordon Wasson, “Seeking the Magic Mushroom,” Life Magazine, 1957.

- “Timothy Leary.” Harvard University, Harvard Department of Psychology, psychology.fas.harvard.edu/people/timothy-leary.

- Martin A. Lee and Bruce Shlain, Acid Dreams: The Complete Social History of LSD (New York, NY: Grove Press, 1992), 75-76; 84-87.

- Erich Goode and Nachman Ben-Yehuda, Moral Panics: The Social Construction of Deviance (Oxford, UK; Cambridge, USA: Blackwell, 1994).

- Tom Wolfe, Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (S.L.: Vintage Classics, 2018).

- Alfred Friendly Jr, “Police Fear Child Swallowed LSD; Brooklyn Girl of 5 Admitted to a Hospital after She Suffers Convulsions,” The New York Times, April 7, 1966, sec. Archives.

- “A Slaying Suspect Tells of LSD Spree; Medical Student Charged in Mother-In-Law’s Death,” The New York Times, April 12, 1966, sec. Archives.

- William Braden, The Private Sea: LSD and the Search for God (London, Pall Mall Press, 1967), 196.

- Erich Goode and Nachman Ben-Yehuda, Moral Panics: The Social Construction of Deviance (Oxford, UK; Cambridge, USA: Blackwell, 1994), 203.

- N.I. Dishotsky et al., “LSD and Genetic Damage,” Science (New York, NY) 172, no. 3982 (1971): 431–40.

- Margalit Fox, “Walter Bowart, Alternative Journalist, Dies at 68,” The New York Times, January 14, 2008, sec. Arts.

- Desert Sun, “Brown Signs LSD Bill to Head off ‘Threat,’” cdnc.ucr.edu, May 30, 1966.

- United States Subcommittee on Public Health, Increased Controls over Hallucinogens and Other Dangerous Drugs: Hearings before the Subcommittee on Public Health, Google Books (U.S. Government Printing Office, 1968).

- Masterclass Staff, “Psychedelic Rock: The History and Sound of Psychedelic Rock,” Masterclass Music, February 2022, https://www.masterclass.com/articles/psychedelic-rock-explained.

- E. Arnett et al., “Habermas on Acid: A Rhetorical Analysis of a Scientific Controversy,” 2008, 7.